Travel in the Industrial Age

The correspondence in the Cope-Evans Family papers is representative of a variety of social and economic trends, both within and outside Quaker Philadelphia. The Industrial Revolution spawned a new era of faster, democratized travel, as “stagecoaches, turnpikes, and steamboats in the 1810s and 1820s, canals in the 1820s and 1830s, and finally railroads in the 1830s and 1840s provided the underlying technology that allowed easy and reliable transportation to be supplied on a mass scale” (Mackintosh 17). By 1821, eighty-five turnpikes had been chartered in the state of Pennsylvania, and a network of paved toll roads was developed leading from Philadelphia to New York, Reading, Harrisburg, Lancaster, Baltimore, and into New Jersey (Richardson 230). The Cope-Evans family was intimately involved in this transportation revolution; Thomas Pim Cope supported the construction of the Pennsylvania Railroad and the Delaware and Chesapeake Canal, in addition to beginning the family packet line. At the same time, that packet line was helping to solidify the family’s socioeconomic standing, the combination of which would allow the Cope-Evanses to travel further than ever before for family, business, or religious reasons.

Resort Life

As the Copes increased their socioeconomic status and travel became more easily accessible, they frequently ventured outside of Pennsylvania for leisure. Vacation culture first arrived in Saratoga Springs and other seaside locales in the 1820s as entrepreneurs promoted the health benefits of the ocean, its gentle breezes, and clean air, but soon evolved into conspicuous displays of wealth and status, of the ability to freely express oneself and to shirk quotidian responsibilities (Sterngass 2-4). Beginning just after the Civil War, the Cope-Evans began annual summer pilgrimages to these resorts; however, the correspondence in the Cope-Evans Family papers does not indicate an enduring presence for a specific location. The family frequently stayed in Cape May, New Jersey; Newport, Rhode Island; Atlantic City, New Jersey; Catskill, New York; and Desert Island, Maine; sometimes traveling to multiple locations in a single season.

The Cope-Evans family appears to have first ventured to Atlantic City in 1862, but did not visit again or with regularity until 1874. While Atlantic City served as a summer destination for many white middle-class Philadelphia residents, the Cope-Evans family regularly stayed at one of the most expensive hotels in the city. According to one study, Hotel Dennis charged between three and three and a half dollars per night in 1887, double the price of most other hotels in Atlantic City as it drew its “patronage almost exclusively from the fashionable and moneyed elements of society” (Funnell 44-45, 48). By staying in such a hotel, the family did not only go to Atlantic City to escape the heat but also to show off.

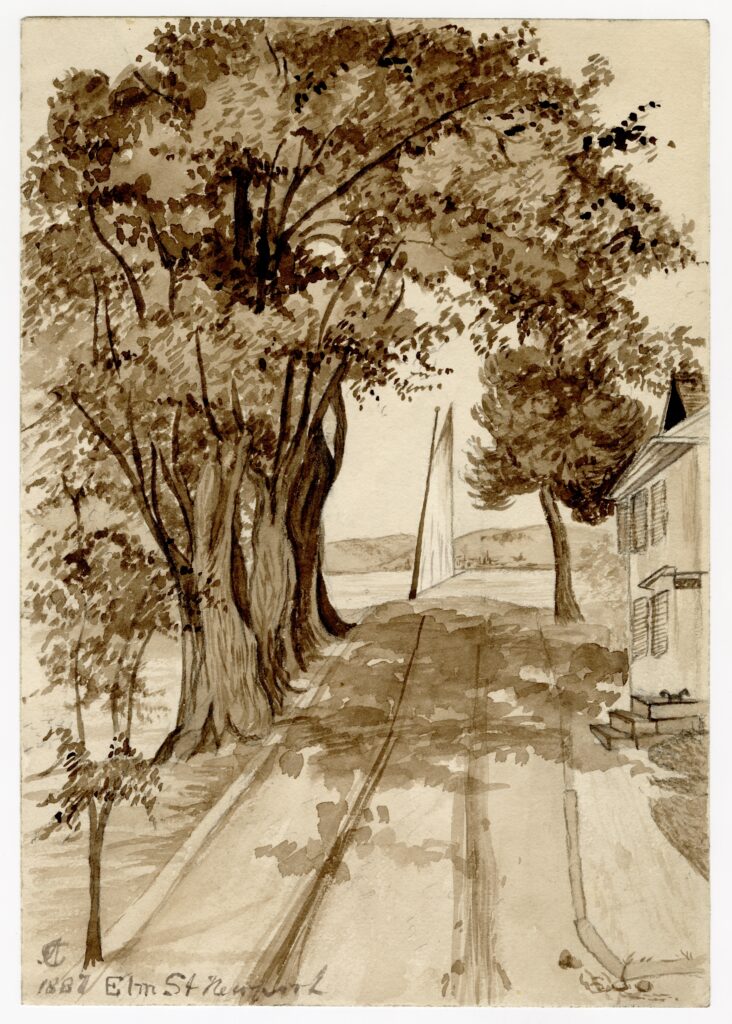

Similarly, in the early part of the family’s pilgrimages to Newport, they often stayed at Bateman’s Hotel–usually referred to in their correspondence simply as “Bateman’s”–a “highly fashionable…enormous three story Colonial-style building” that hosted the likes of Mark Twain (Roche 24). Yet the family, despite their relative wealth, was still not among the most prominent sojourners as they appear separate from both Twain’s intellectual scene and the upper elite who had abandoned hotels in favor of constructing grandiose cottages (Sterngass 188). Their venture into hotels was relatively recent, as, before the Civil War, when the Cope-Evanses only occasionally visited and even then at the conclusion of the season, they stayed at a boarding house. Then, they traveled by sound boat in the middle of the night–the only time the boats stopped in Newport–and their favorite playground was eventually privatized by a more wealthy cottager (Reminiscences of My Youth). As late as 1888, the Cope-Evanses even visited Easton’s Point, known among that upper class at that time as “the Common Beach” (Sterngass 193).

Still, the family attempted to keep up appearances in Newport, soon entering the cottage scene themselves. In 1892, Anna Brown Cope and Theophilus Stork would construct Fowler’s Rocks in nearby Jamestown, featuring a view of the bay and a caretaker’s cottage (Rhode Island Historical Preservation and Heritage Commission 56). Mossgiel was also a frequent destination, though it is unclear if the cottage was owned by the family; Bateman’s became a rarity.

Rachel Cope Evans would frequently stay at Fowler’s Rocks with her sister and mother, Anna Stewardson Cope, until 1910, but the relative remoteness of the summer home occasionally proved to be a challenge. Writing in the first September the house was open, Anna Stewardson Cope relates that “Walter [Kane] seems to have an idea that Anna is too far out of the way, which is quite a mistake, and she [Anna Cope Stork] felt disappointed.” This disappointment is indicative of one of the key reasons the Cope-Evans family traveled in the summer: to connect with extended family and friends as they escaped from the rhythms of reality. The family sailed, had picnics, and swam in the local beaches. Here, their surviving photographs are more candid than the carefully staged portraits at Connymead and Awbury. Annette Cope painted idyllic scenes of quiet streets, cottages, and boats.

To be able to escape reality in this manner was a luxury, even if the family refrained from the more ostentatious displays of wealth that sometimes dominated Newport culture. Though industrialization helped to create more time for leisure and provided for various means of transportation, not everyone was able to vacation, let alone for an entire season. The Cope-Evans family’s own vacations were facilitated by the nurses they brought with them that took care of the children and allowed the adults to relax, in addition to the numerous hospitality workers that took care of their every need.

International Travel

While the majority of the Cope-Evans family’s non-business-related travel was to these domestic seaside resorts, the end of the Civil War also saw an increase in travel abroad. Alexis T. Cope and Rachel Cope Evans each honeymooned in England, their ancestral home, following their respective weddings in 1875 and 1873, sometimes connecting with family along the way. But just as Newport often served as a place for family to connect and for children to play, European travel was more frequently reserved for unmarried family members.

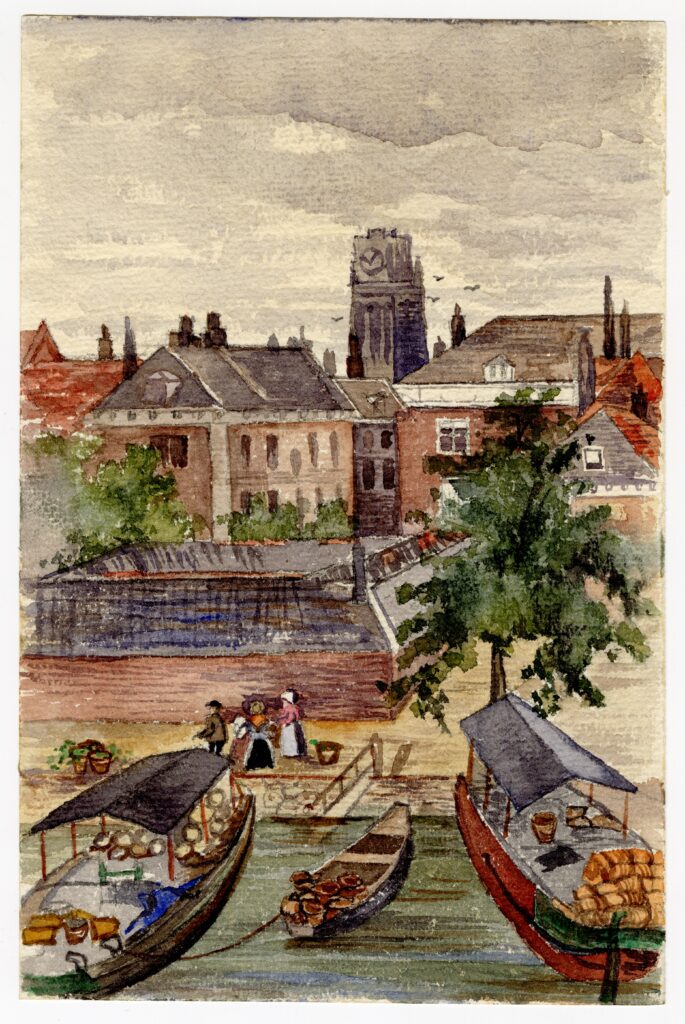

Clementine, Annette, and Caroline Cope, the three unmarried daughters of William Drinker Cope of Connymead, each traversed Europe with varying degrees of regularity beginning in 1869. Whether together or separately, or meeting up at points along the way, the sisters each followed the traditional “Grand Tour” itinerary, usually visiting Switzerland, France, Germany, and Italy and occasionally venturing to England and Scotland.

Though the Grand Tour began as a typically male endeavor in which British men reaching adulthood would embark on a rite of passage, by the 1840s, “upper- and upper-middle-class women [in the United States] began challenging the purely domestic image that tied them to home and hearth” (Harvey Levenstein, qtd. in Beatty 2). Young women were especially well-suited to embark on transatlantic journeys as they did not face the same capitalist pressures as their male counterparts; the Connymead sisters were among the first Copes to come of age in this period and to truly benefit from the generational wealth established by their grandfather.

But European travel was about more than just finances. Just as the British predecessors used the Grand Tour to announce their place in society, American tourists were required to possess the knowledge to communicate with each country’s residents and to intelligently discuss the art they encountered. Upper-class men and women alike “were offered a European-based curriculum and were well educated in European art, music, history, literature, and languages” (Beatty 7). Clementine, likewise, studied French, and her scrapbook documents an interest in British royalty and Europe as a whole from an early age. Clementine Cope’s diary of her travels around Italy between 1879 and 1880 similarly documents her interests in Roman mythology, art and sculpture, and ancient history. She frequently cites the work of art historian John Ruskin, indicating at least a self-taught expertise in the subject.

Individual interests informed the sisters’ activities. At least one member of the trip usually kept those at home informed of their travels, reporting their personal evaluations of the sites. As she did in Newport, Annette Cope painted outdoor scenes. Clementine visited art museums and ruins. As she traveled, she may even have sought to follow Ruskin’s suggestions in guides such as Mornings in Florence for key works of art and monuments to visit. Larger groups would engage in outdoor activities.

Still, Europe sometimes failed to live up to Clementine’s expectations as she carefully evaluated its landscape, art, and people. Writing in 1869 from the French Alps, she tells her brother Alexis that

A great proportion of the travellers in Switzerland seem to be english, & not very interesting generally a good many of the “swell” variety – both male & female seem to abound, & they amuse us not a little with their affectations….The people of the village of Chamouni we conclude rave also for it seems to be the noisiest little town we have been in. Under my window they are gabbling & talking ceaselessly & singing & howling & yowling besides just for the pure pleasure of making a noise, I think. It is so entirely out of keeping with the spirit of the place that it provokes me, & interrupts my meditations besides – I wish they wd. be quiet but they dont know what quiet is. The excessive garrulity of these foreigners is very tiresome I never felt more like saying “By Jabbers” [slang, “By Jesus!”] in my life, than I have lately. They seem to just talk on & on like perfect machines.

She similarly found some works of art in Italy to be disappointing. Clementine, then, separates herself both from other tourists and from local residents, positioning herself as the true arbiter of propriety and artistic merit, a tourist above all others. She was not alone in her distaste for the people of Europe; in Italy, some American women “struggled with the disquietude they felt when the Catholic city and the contemporary city impinged on their experience of ancient ruins” (Beatty 157). Having imagined Europe for decades, women like Clementine would have found it difficult when their dreams did not completely match reality.

These imaginings, of course, were based on Clementine’s own socioeconomic, religious, and cultural background. How did her education and generational wealth inform where she decided to visit and what she deemed interesting?

Bibliography

Beatty, Bess. Traveling Beyond Her Sphere: American Women on the Grand Tour, 1814-1914. Washington, D.C.: New Academia Publishing, 2016.

Funnell, Charles. Virgin Strand: Atlantic City, New Jersey as a Mass Resort and Cultural Symbol. Dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, 1973.

Mackintosh, Will B. Selling the Sights: The Invention of the Tourist in American Culture. New York University, 2019.

Richardson, Edgar. “The Athens of America, 1800-1815.” In Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, Russell F. Weigley et al. (New York: W. W. Norton, 1982), 208-257.

Roche, John. “Making a Reputation: Mark Twain in Newport.” Mark Twain Journal 25, no. 2 (1987): 23-27.

Rhode Island Historical Preservation & Heritage Commission. Historic and Architectural Resources of Jamestown, Rhode Island. 1995.

Sterngass, Jon. First Resorts: Pursuing Pleasure at Saratoga Springs, Newport & Coney Island. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univers